Feb 28, 2018 @ 17:13

Extirpate – to destroy or remove (something) completely.

It has been a story of frustration and dogged determination to save the Lake Superior Woodland Caribou on Michipicoten Island from extirpation. The Woodland Caribou that live on the shores of Lake Superior have been harder and harder to find. In fact, Woodland Caribou are considered a ‘species at risk’ with Ontario creating a Woodland Caribou Conservation Plan in 2009, nine years ago. Some very important statements were made in that Plan:

“4.1.4 The Lake Superior coastal population will be managed for population security and persistence. The focus will be to protect and manage habitat and encourage connectivity to caribou populations to the north.”

“5.3 Ontario will review the feasibility of caribou translocations (i.e. the trapping and transferring of animals within Ontario) as a caribou recovery tool for very specific situations, including an assessment of risks and the development of criteria and guidelines, if appropriate. This review will examine lessons learned from past experience in Ontario and elsewhere as well as disease transmission and regulatory considerations. Translocations have been shown to be successful at establishing caribou populations in very specific situations, such as predator-free islands.”

“5.5 Within the geographic distribution of caribou, populations of predators will be managed primarily by managing habitat and the associated roads to reflect natural forest conditions. This will include the management of land and resource uses to maintain naturally-occurring low densities of prey (e.g. Moose, White-tailed Deer) and predators. Ontario will assess the feasibility and effectiveness of directly and indirectly influencing predator densities in very specific situations, and develop criteria and guidelines for managing the prey-predator balance as required.”

Kutcha (2012) “Bottom-up and Top-down Forces Shaping Caribou Forage Availability on the Lake Superior Coast”

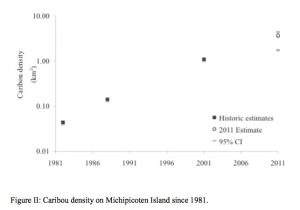

With those public statements, it is very difficult to understand how the caribou on Michipicoten Island could be in the situation they are in today. From an estimated population of 680 in 2011 to perhaps 30 in December 0f 2017.

The saga of the Woodland Caribou began with the realization that the Pukaskwa National Park caribou stocks showed a serious decline. Estimates ranged from 31 in 1979, to 9 in 2003 and extirpation not far away. To protect the species, from 1982 to 1989, Woodland Caribou Restoration Projects took place with Michipicoten, Montreal Island, Bowman Island/St. Ignace Island, and Lake Superior Provincial Park were selected as new homes for caribou from the Slate Islands which were overpopulated with caribou.

In 1984, 10 were released on Montréal Island, 14 were observed in 1988. In 1993, 16 caribou were seen, but then wolves reached the island in 1994, killing some and the others left the island.

In October 1985, six caribou were brought to Bowman Island, where wolves and moose were present, but the transplant failed due to predation (1986). By April 1986, 4 of 5 collared caribou perished within 6 months (Bergerud and Mercer 1989). Bowman Island is adjacent to St. Ignace Island where caribou had persisted into the late 1940s.

In the fall of 1989, 39 caribou were translocated from the Slate Islands to Lake Superior Provincial Park (Gargantua Peninsula). By the following summer, all but 1 of the 17 radio-collared animals were either killed or died and were scavenged by wolves. Despite the high density of moose and wolves in Lake Superior P.P., the herd had persisted in the coastal zone near Cape Gargantua and Dixon Island for approximately 20 years. Three caribou were last observed in 2007 (Bergerud et al. 2007), but there has not been any evidence since and it appears this herd is extirpated.

The only successful story was the Woodland Caribou translocated to Michipicoten Island. The herd had grown to nearly 1,000 in 2014. The underlying thread for failure in the other populations was the predation by wolves.

In addition to the losses of the other transplanted caribou, an aerial survey in 2015/16 from 20 km east of Nipigon to approximately half-way through Lake Superior Provincial Park didn’t record one caribou sighting. Only four groups of “caribou sign” were reported, all recorded west of Neys Provincial Park. This federal Access to Information Request revealed that even after seeing no caribou, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry and Parks Canada reported that there were 55 caribou on the north shore of Lake Superior.

The 30-year success of the Michipicoten herd wasn’t guaranteed though. Three, possibly four wolves came over in the winter of 2013/14. In February/March 2015, the MNR collared these wolves, established trail cams at the den and a study was well underway.

Their objectives:

- assessment of future wolf and caribou population trends

- assessment of potential emigration of wolves from the island

- quantification of wolf foraging activities with respect to caribou

- determine the ultimate impacts of wolf presence on caribou, vegetation, and other vertebrate species, and

- attract and develop external research partners and funding to support a multi-faceted, multi-trophic level, long-term research project.

Well, by June 2015, it was obvious from that this research project led by Brent Patterson, the three wolves were doing well. In March, the male weighed in at 120 lbs and two females at 103 lbs. An average male would be 70/75 lbs. At that time early indications were of possible ‘high-grading’ by the wolves because of their bountiful prey. The bone marrow was tested for fat content – a means of assessing the caribou’s health and likelihood of winter survival. The impression was made that many of the caribou that had been killed wouldn’t have survived the winter – a natural culling. One should keep in mind though, that collaring began in early March 2015, and spring was just around the corner. A wolf can do the traverse from Michipicoten Island to Pipe Harbour on the mainland in about 3 hours, and telemetry recording one traveling back and forth. It wasn’t clear at that time, but there may have been a fourth wolf, a female.

At that time as well, the source population on the Slate Islands was diminishing. Today, the MNRF estimates that there may be 2-4 bulls remaining. Without any females to breed with – this herd is sexually extirpated – dead.

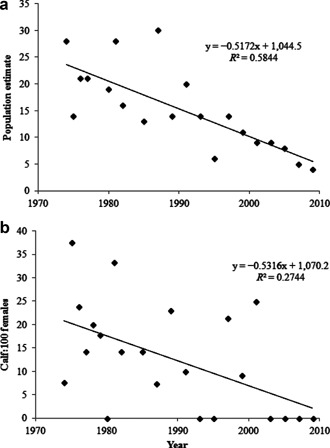

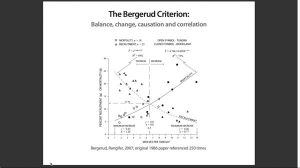

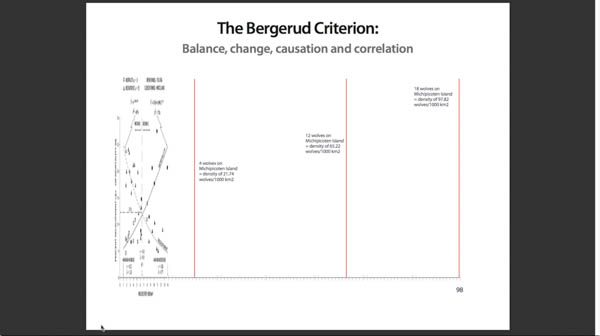

Sadly, this research project damned the population on Michipcoten Island and possibly the Lake Superior Woodland Caribou to extinction. Despite well-respected research, the number of wolves was allowed to increase reducing the herd dramatically. The Bergerud Criterion states, “A caribou population cannot be sustained if the wolf population density in the same area exceeds 6.5 wolves/1000 km2″. If only two wolves were present, the threshold would be exceeded on Michipcoten Island.

Sadly, this research project damned the population on Michipcoten Island and possibly the Lake Superior Woodland Caribou to extinction. Despite well-respected research, the number of wolves was allowed to increase reducing the herd dramatically. The Bergerud Criterion states, “A caribou population cannot be sustained if the wolf population density in the same area exceeds 6.5 wolves/1000 km2″. If only two wolves were present, the threshold would be exceeded on Michipcoten Island.

Apparently, the MNRF has continued the study of wolf predation and caribou because of a single factor, beaver.

Michipicoten Island has a substantial population of beaver, that is also a food source for the wolves. A paper was to be presented at the Conservation and Ecology of Mammals – Carnivores (September 26, 2017) but was canceled. The abstract from “Wolf Recolonization Threatens Caribou Persistence on Michipicoten Island, Ontario – Brent R. Patterson; Arthur R. Rodgers; Jen Shuter; Carol Dersch; Steve Kingston; Evan McCaul” was revealing. “Abstract – However, despite their declining status in most mainland areas, caribou have remained abundant on some predator-free coastal islands in Lake Superior, Ontario. One such place is the relatively undisturbed 188 km2 Michipicoten Island, which was naturally recolonized by 4 wolves via an ice bridge in winter 2014. Our objective was to determine the impact of wolf predation on caribou in this system where wolves are the only substantive predator of caribou but also prey on an abundant beaver (Castor canadensis) population. Specifically, we are testing the hypothesis that where wolves are present, predation rather than food abundance is the primary factor limiting caribou abundance. We estimated caribou numbers via a combination of aerial quadrat surveys and camera trapping, and estimated that there were approximately 450 caribou present on the island in autumn 2014, 6-8 months after wolf recolonization. By winter 2017 wolf numbers had at least tripled and caribou abundance had declined by ≥ 60 %. We expect wolves to remain abundant as caribou continue to decline because beaver remain abundant and represent a substantive alternate prey source. Population models suggest that extirpation of caribou as soon as 2020 is possible. Although preliminary, these data support Bergerud’s 1974 contention that predation rather than a shortage of winter lichens may be the primary factor limiting abundance of woodland caribou.”

Did the desire to prove this hypothesis damn the caribou of Michipicoten Island?

With the collapse of the Slate Island population and the subsequent killing off of the Michipicoten Island population by an increasing wolf pack – did the MNRF wantonly disregard the statements that begin this article. One could cynically say that this may never have been found out; if, the people with cottages on Michipicoten Island hadn’t noticed the severe decline and were determined to save the caribou from extinction.

This pressure has resulted in the collaboration of Michipicoten First Nation, MNRF, Muncipality of Wawa to rescue some of the Michipicoten Island Caribou. Ten were transferred back to the Slate Islands (1 was euthanized after transfer for unknown reasons). This population is still at risk, and will always be at risk, as it has been demonstrated that wolves can reach the island.

More pressure resulted in a second transfer of five to Caribou Island, a nature preserve close to the US/CDN boarder south of Michipicoten Island. These caribou were not sedated, and the transfer was done without incident. The goal was to have 6 animals moved, but efforts stopped after 5. However, to the partnership it seems that the cost of translocating seems to be the barrier. It is recommended that at least three bulls in every group of 20 caribou be considered for genetic diversity and simple survival. To that end, it would simply increase the opportunity for success, if all the caribou were moved.

The mention of cost is very difficult to understand. What is the cost of tracking collars for the wolves, telemetry, software, helicopters, staff when balanced against the survival of a species at risk? The MNR had and still has a duty to protect the Michipicoten Island Woodland Caribou/Lake Superior Woodland Caribou. Wolves are easy to move, are not protected, not at risk of disappearing forever.

There may still be caribou on Michipicoten Island – surely hiding terrified and running for their lives because the 20 some odd wolves are hungry. The beaver, the alternate source of food for these wolves – is safely ensconced in their lodges for the winter. It doesn’t take much imagination to describe what will happen to the wolves. Starve, die a lingering death, kill each other and unborn pups.

This experiment, desire to prove a hypothesis… has damned both the caribou and the wolves in one fell swoop. From the abstract, “We expect wolves to remain abundant as caribou continue to decline because beaver remain abundant and represent a substantive alternate prey source. Population models suggest that extirpation of caribou as soon as 2020 is possible.”

There are concerned individuals working hard to preserve what is left of the Michipicoten Island Woodland Caribou/Lake Superior Woodland Caribou. They continue to put pressure on the MNRF through Freedom of Information requests to uncover the costs and extent of damage from the proving of this hypothesis.

Visit http://lakesuperiorcaribou.ca/ for more information.

We know the problem, yet continue to spend large sums on research that could be used for adaptive management (sensu Walters & Hilborn, 1978). We should be counting and radio tracking wolf populations. The problem is not the habitat, it is predation; habitat per se does not kill caribou. ~ Arthur T. Bergerud (2007)

- Monday Morning News – June 30 - June 30, 2025

- Saturday Morning News – June 28th - June 28, 2025

- Rock Island Presents – Michel Neray House Concert Tonight - June 27, 2025

Wawa-news.com You can't hear the 'big picture'!

Wawa-news.com You can't hear the 'big picture'!

From a Sault Star article Tuesday evening, “MNRF said Tuesday it plans no “further relocations at this time” to Caribou Island.

“We are not planning any further relocation at this time,” ministry spokesperson Maimoona Dinani told The Sault Star Tuesday. “Through our translocations of caribou to the Slate Islands and Caribou Island, we believe we helped to establish two backup populations of caribou. These are sound interim measures to preserve the Lake Superior coastal range population while we involve others in a broader discussion on longer-term decisions. We will continue to monitor the translocated populations to ensure sustainability of the herd.””

Well, Ms Dinani, how much money will be spent to monitor those two fragile populations. Hopefully, as much as is being spent to keep track of all the wolves as they become overpopulated thanks to all those delicious beaver.

Amazing how many contributors to the study will get “recognition” for being part of this expensive experiment to prove what was already known forty years earlier. Not one of the five thought this was contrary to the intent to manage prey-predator numbers to preserve the caribou as per the 2009 plan.

On a another note, the wolves may not starve after all. I have been told that the wolves can begin feeding on the beaver early in February as the first kits born , having been kicked out of the den to make room for the next batch and inexperienced in gathering food for their winter dens, run out of food and must come out to find some which delights the wolves.

Canadian conservation groups should consider fund raising to enable translocation ofa few more male caribou this would increase genetic diversity and chance for long term survival. How can state supported scientists stand by and donothing while the extinction of A sub- species is allowed to occur? Scientists have an obligation to all wildlife not just their narrow field of study….they vaguely remind me of the excellent science done in Germany in the 1930s

Tom Allum

Seems on mainland at least, there were plenty of both caribou and wolves for many centuries. Perhaps there is an underlying problem, unmentioned here, that is not being adequately addressed? I don’t know what that might be.

Ontario’s wolf population is estimated at approximately 10 wolves per 1000km not including coyotes and coywolves.. If 6.5/1000 is too many for caribou to surevive it’s no wonder ungulate populations are crashing across the board.