In 1960, while working for Shell Oil in Jasper Park, Alta., I bought a weekend edition of the Globe and Mail. Inside was a 30-page insert advertising secondary school teaching positions at every school board in Ontario. The postwar baby boomers were headed to high school. I had often considered teaching and, to my astonishment, discovered that having a university degree and agreeing to take a university summer course were acceptable qualifications.

I phoned the principal of a high school that had included a “teacher’s house” in the job description. After a very pleasant interview, he offered me a science and math opportunity on the condition that I pass an eight-week summer course at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. I would quip later that, had I taken a nine-week course, I might have qualified as a brain surgeon!

Michipicoten High School was situated in Wawa (Anishinaabemowin for “wild goose”), a mining town of 5,000 located on the north shore of Lake Superior, some 200 miles north of Sault Ste. Marie and 300 miles east of Thunder Bay. When I accepted the job, the principal explained that, on my way from Alberta, I would have to drive to Queen’s via Windsor, since Highway 17 from the Sault to Wawa might not be completed until Labour Day.

Luckily, Highway 17 opened to cars during the last week of August. So, on the day after Labour Day in 1960, I was nervously teaching science and math to Grade 9B in my own homeroom. A week later, the school’s 250 students were bused down to Highway 17, just outside of town, for the ceremonial ribbon cutting and opening of the new route by Ontario Premier Leslie Frost and federal Minister of Trade and Commerce George Hees.

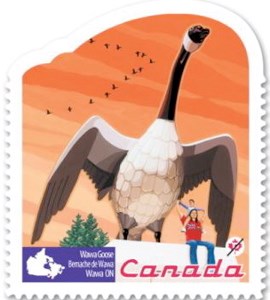

On a concrete plinth overlooking this ceremony stood Wawa’s new 28-foot-high goose monument, erected to celebrate the new highway. It was made of chicken wire and plaster. Little did I realize that my life would be forever entwined with that giant statue.

My four years in Wawa were magical. I loved teaching and enjoyed the instant feedback from my students — something that rarely happens in a large corporation.

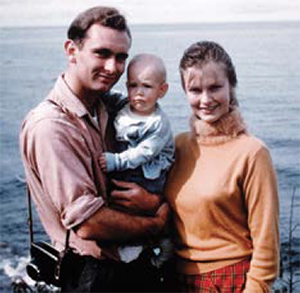

Two of my three children were born in Wawa, and our family became totally involved in the culture and politics of the community. I directed school musicals, coached track, and even acted with the town drama club. In 1962, at the end of my second year, I ran for municipal alderman and, thanks to a huge main-street parade engineered by my students, got elected.

Around election day, Goose 1, weakened by rust and the occasional shotgun blast, collapsed onto the highway in a pile of chicken wire and plaster. The townsfolk asked the council to replace it. The job of finding Goose 2 was delegated to me as a neophyte councillor.

Where do you buy a 30-foot-high Canada Goose? Nowhere, it turns out.

So with the help of my artistic wife, we held a design contest instead and selected a four-foot-high wrought iron model, submitted by Dick van der Clift, an ironworker from the Sault. Dick then constructed the full-size Goose 2, which was erected in 1964. Cost: $5,000. Goose 2 became famous. Its image was even included on Canada Post stamps.

So with the help of my artistic wife, we held a design contest instead and selected a four-foot-high wrought iron model, submitted by Dick van der Clift, an ironworker from the Sault. Dick then constructed the full-size Goose 2, which was erected in 1964. Cost: $5,000. Goose 2 became famous. Its image was even included on Canada Post stamps.

I left Wawa in 1964 for a principalship on Manitoulin Island and, coincidentally, passed Goose 2 travelling on a flatbed truck on its way to Wawa, where it proudly stood for 53 years.

In 1991, after 31 years of teaching in other Ontario towns and for the Department of National Defence in Europe, I retired to Salt Spring Island in British Columbia. I was greatly honoured in 2017 to be invited by the mayor of Wawa to preside over the unveiling of Goose 3 (a more expensive model at $250,000), the stainless-steel replica of Goose 2 on Canada’s 150th birthday.

This article first appeared in RTOERO’s Renaissance magazine, Summer 2021 issue. https://rtoero.ca/resources/renaissance/

- Friday Morning News – February 13 - February 13, 2026

- Hwy 11 & 631 remains closed - February 13, 2026

- WFD Responds to Fire on Broadway Avenue UPDATED - February 13, 2026

Wawa-news.com Local and Regional News

Wawa-news.com Local and Regional News